AFUL Cantor - Classical formula perfected

It is not an exaggeration to say that I have been waiting a few years to finally write this review article. The reasons were twofold. Firtsly, the product itself took a long time arrive: it has been more than one year and multiple releases between the moment AFUL teased their flagship 14-driver IEM Cantor and time when it is finally here on my desk. Secondly, ever since the time I started reviewing IEMs a few years back, I have been waiting for someone, somewhere, somehow, to make that IEM, the one that makes me say: “This is it!”. Needless to say, it has been a long wait.

With this context, you would excuse me if this review is somewhat more verbose and introspective than usual. I’ll highlight the main points to help you skim, but if you would indulge me, grab a cup of something and get comfy. We are in for a ride.

Forewords

- What I look for in an IEM is immersion. I want to feel the orchestra around my head, track individual instruments, and hear all of their textures and details. I’m not picky about tonality, as long as it is not make the orchestra, violin, cellos, and pianos sound wrong.

- I rate IEMs within with a consistent scale from 1 (Poor) to 3 (Good) to 5 (Outstanding). An overall ranking of 3/5 or above is considered positive.

- Ranking list and measurement database are on my IEM review blog.

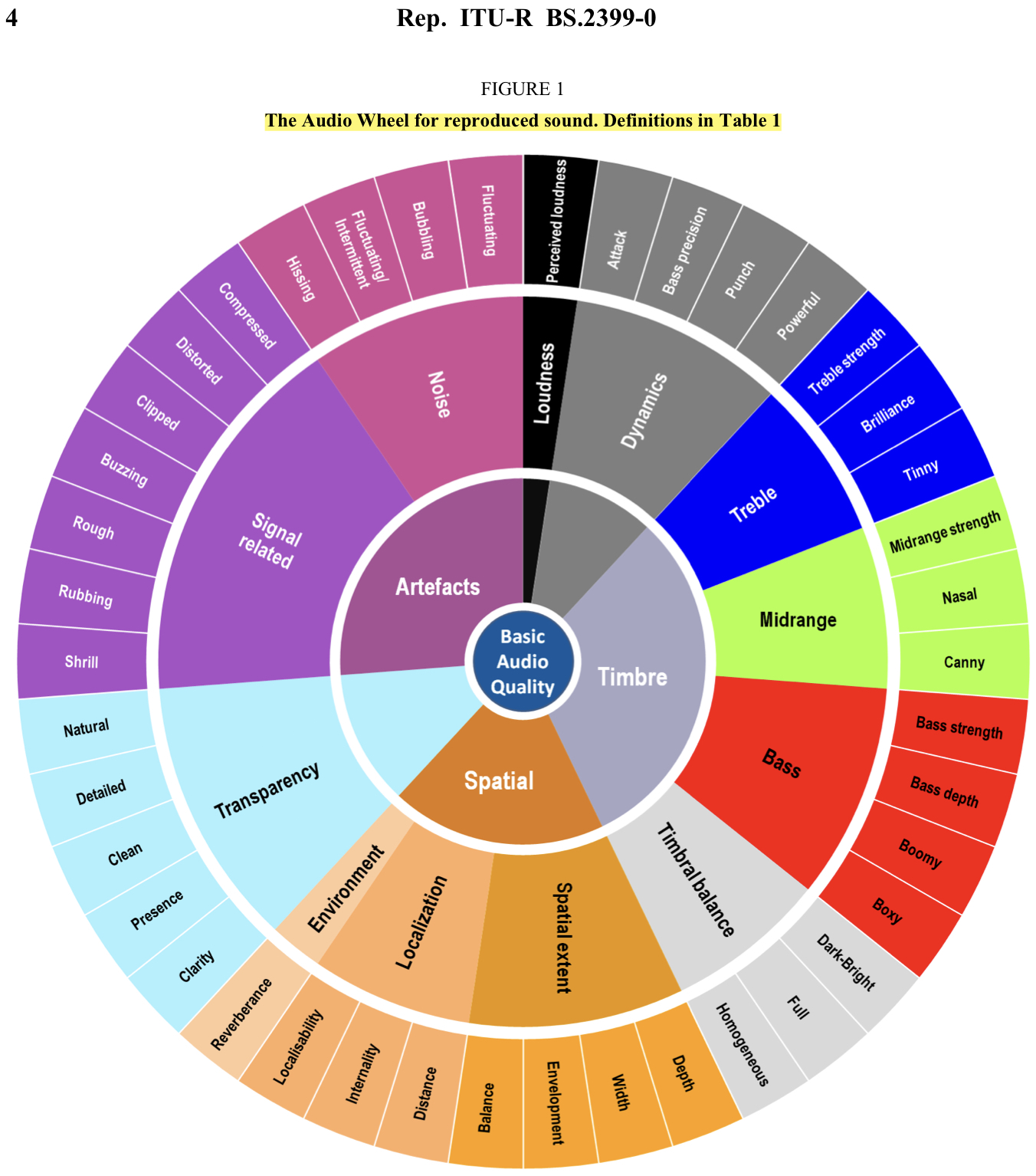

- The terminology for subjective impressions in this review is based on the Audio Wheel for reproduced sound defined in the technical report ITU-R BS.2399-0

- This review is based on a review sample purchased at a discount from Hifigo (Thank you!). I have no affiliation with or financial interest in AFUL and Hifigo.

- The unit retails for $799 at the time this review was published. Unaffiliated link: Hifigo

In pursue of the ideal

You are going to see quite a few superlatives in this review, such as “ideal”. Therefore, I think a short detour to lay the groundwork would be beneficial. Let’s talk about the “ideal” IEM. Before doing so, we need to revisit a related concept, the “perfect IEM”. A fellow reviewer once said that a “perfect” IEM, the one that has no fault to the ears of any listener, is impossible because people’s requirements are contradictory. For instance, an IEM can not simultaneously be perfect for a “basshead”, a “treblehead”, and a reference because the very act of tuning the frequency response toward bass or treble would turn an IEM away from a reference “flat” response, and vice versa.

Now, I have nothing but full agreement that a “perfect” IEM is an impossible self-contradiction. However, I (stubbornly?) believe that an “ideal” IEM is possible and actually should be pursued. Bold claim, I know. This claim begs the question: what is an “ideal” IEM?

To me, in order to talk about an “ideal” IEM, we need to take a step back and look at the IEMs themselves. What are they? What is their “point”? To me, IEMs serve but one purpose: faithfully translating electrical signals into sound waves. In other words, they are “screens” or “monitors” for the ears to “see” the audio content, be it music or movies or video games, as faithfully, clearly, and detailed as possible. They don’t have to be to be “soulful”, just as you wouldn’t ask your TV to be “soulful.” If they do a good job, the “soul” of the content would be laid bare for you to enjoy.

The implication of my conceptualisation of IEMs is that an ideal IEM, at least to me, is pretty much define-able and thus not a contradictory but a realistic target to shoot for. In other words, an ideal IEM is the one that faithfully reflects the source material (a.k.a., “flat” response), with an extreme level of resolution down to the minute spatial cues and details. An ideal IEM should be so crystal clear that you can track and follow any individual element in the mix without difficulty, yet you can also sit back and see how the whole mix come together, without losing sight of components. It should be so detailed that voices and instruments in the mix feel real. The spacial cue should be so accurate that you can pin point both the direction and distance of the sound sources in a virtual sound field crafted by an audio engineer or a game engine. And it should do all of this without sounding like ice picks in your ears.

What I find interesting is that there appear to be a strong relation between the actual construction and engineering effort behind an IEM and how close it is to the vision of an ideal IEM. For example, a smooth and even frequency response helps an IEM avoid the dreaded masking effect, allowing details to shine. The ability of an IEM to maintain smooth and audible response deep into the upper treble correlates to micro details and reproduction of spatial cues. A better cross-over design with minimal overlap between drivers tend to keep the sound clean and detailed. Cutting back on the use of dampening foams and filters tends to keep note attacks snappy and clean, further improving clarity, instrument separation, and details. So on and so forth. Engineering and ingenuity, not magic, power the “ideal” IEMs.

Can we ever reach an ideal IEM? It’s hard to say, since we need know what the maximum level of information crammed into recordings that we can extract. In my experience, whenever I think we are “there”, the next level is just around the corner, being perfected on the workbench of an IEM engineer somewhere. There has always been the next level. So, the path towards an ideal IEMs forks into two branches: (1) given an unlimited budget, how close can we get to the top, and (2) given a limited budget, how far can we go. In other words, the first path is the battle for “State of the Art” (SOTA), and the second path is the battle for productionalisation of SOTA, to make it accessible to as many listeners as possible. Both are interesting and challenging.

And that brings us back to the topic of the article today, the AFUL Cantor.

_____

_____

General Information

As you know, the “General Information” section of my review is the time to geek out about the engineering and technologies of an IEM. Buckle up, we are going to stay here for a while.

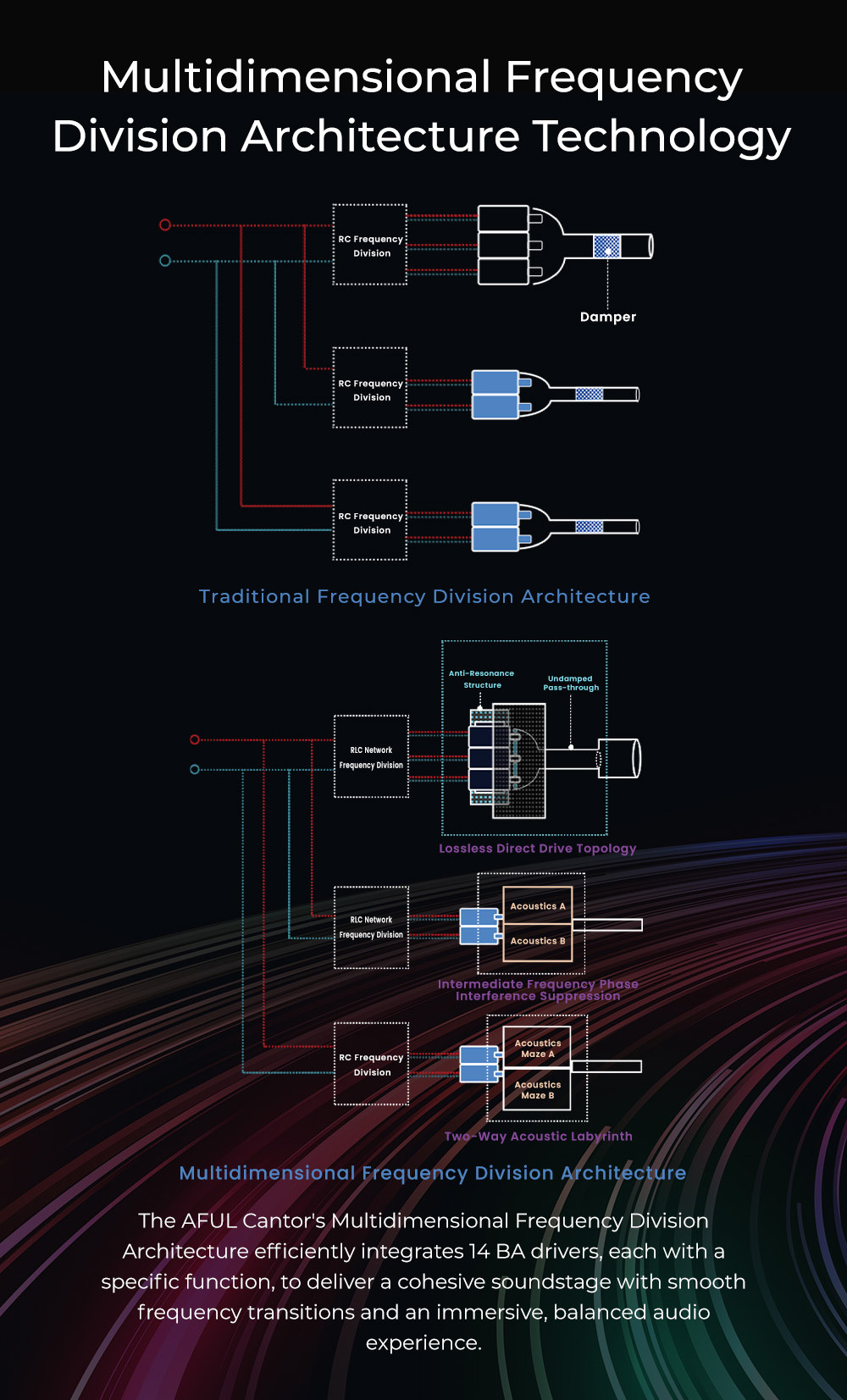

Let’s start from the top. Cantor is a 14-driver IEM that features a 7-way electrical crossover, 5-way mechanical crossover design with minimal overlaps. It means the incoming audio signal is split into 7 parts, each of which is fed to a pair of Balanced Armature (BA) drivers (thus 7x2=14BA drivers in total). The output sound wave of 7 driver pairs are fed into 5 separate sound paths, which further shape and tune the final response. If you geek out about IEM as much as I do, I think you would find the crossover design of Cantor a rare beast, even amongsts SOTA IEMs. In general, more sophisticated crossover provides tuners a precise control over the frequency response of the IEM. It also ensures that each driver produce sound within their optimal frequency band which, in my experience, leads to stronger clarity, instrument separation, and detail retrieval. Moreover, it also allows tuners to do some interesting tricks, one of which AFUL utilised to implement the bass response of Cantor.

The bass of Cantor is handled by what AFUL calls “Dual Channel Acoustic Maze Technology.” Personally, I call this technology “splitting BA woofers.” It operates based on two main ideas: (1) electrically splitting the bass frequencies into subbass (10-100Hz) and mid-bass and feeding these parts to two different sets of BA woofers; and (2) connecting the subbass woofers to a long acoustic tube to create Helmholtz resonance in the subbass frequencies, amplifying this region. The end results is a bass response that is snappy and agile in the midbass attack whilst maintaining the necessary “weight” and physical sensation in the subbass. Such “weight”, when done right, contributes the illusion of bass elasticity that many of us crave. Keen readers might find the resemblance between Cantor and Subtonic STORM regarding “splitting BA woofers”. (Though, admittedly, the “splitting” of Cantor is not as extreme as STORM, which actually features two BA woofers from two different types, combined into one composite driver.)

The treble of Cantor is also quite extreme in terms of driver count and technological design: 6 BA drivers are carefully controlly electrically before outputing the sound into what AFUL calls “Non-Destructive Direct Drive Topology Technology”. Essentially, it replaces the usual tube-and-filter design with a new 3D printed bracket and sound path that is designed to eliminate resonance. This technology helps flattening the dips and peaks in the treble which, in my experience, a main causes of harshness and loss of treble details.

Let me elaborate on this point. When your treble response has strong peaks with valley in between, you need to choose one of two options when setting your listening volume: set it low so that the peaks would not hurt your ears at the cost of details in the valleys, or set it high so that you can hear all the details in the valleys at the cost of harshness and acoustic masking from the treble peaks. By smoothening the treble, Cantor overcomes these problems, without relying on acoustic filters that tends to have negative impact on perceived dynamic and resolution of an IEM.

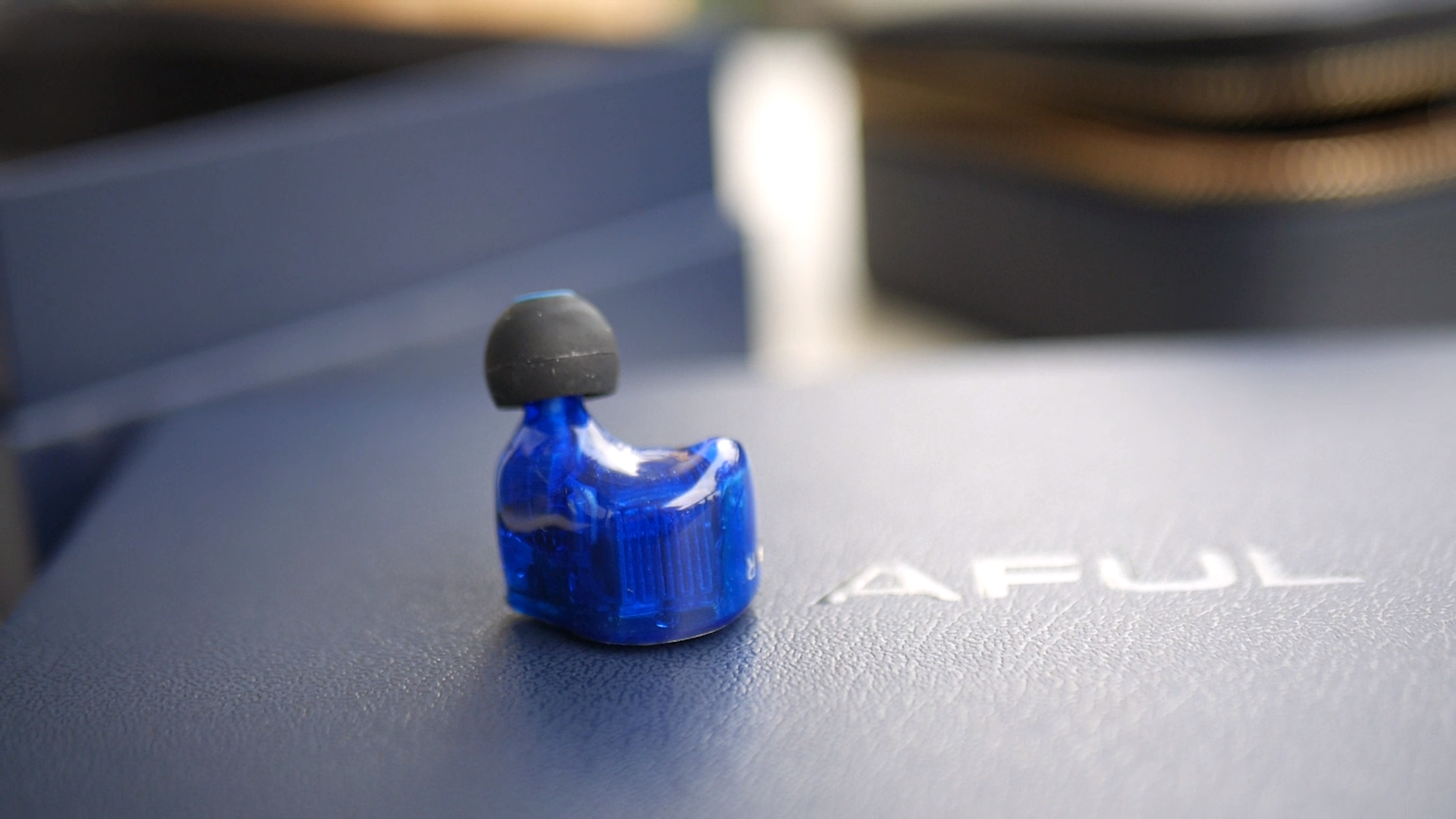

Another peculiar design to aid the treble response of Cantor does not reside inside the earpieces, but on the nozzles themselves. Yes, I’m talking about the scary-looking metal tubes extruding from the nozzles of Cantor. The purpose of this metal tube is to maintain the shape of the sound path all the way from the tweeter array to the end of the ear tips to preserve all of that treble information goodness. In principle, this design is quite similar to the Pentaconn Coreir ear tips. The difference is that the metal tube is integrated into the IEMs rather than on the ear tips.

Compared to the bass array and tweeter array, the midrange design of Cantor seems relatively tame. Dubbed as “Intermediate Frequency Phase Interference Suppression” technology, the midrange driver array of Cantor consists of 4 drivers, splitted into two groups. Each group handles a different frequency band and uses a separate sound path before merging together at the nozzle.

To round-off the the technology galore, AFUL brings a “High-Damping Air-Pressure Balance System” to Cantor. Simply put, Cantor has a pressure release vent in the nozzle to balance the air pressure in the ear canal in order to reduce discomfort (a.k.a., “pressure build up”) in long listening session. However, the dampening of this pressure release mechanism is quite high, so the noise isolation of Cantor does not reduce as much as, say, 64 Audio IEMs with the APEX pressure release vents. At the same time, it does not release pressure as much as the APEX vents.

Non-sound Aspects

Packaging and accessories: The packaging of Cantor is quite straightforward, if not minimal, though not devoid of flair. The artwork on the outer cardboard sleeve is a simple product photo any “show-off” about the engineering packed inside. I have but one complaint here: the font used by the word “Cantor”. Why are the width of the letters not even??? It would be understandable (though not really acceptable) if the designer has to squeeze the text to fit on the faceplate, but why the text is also squished on the cardboard box?

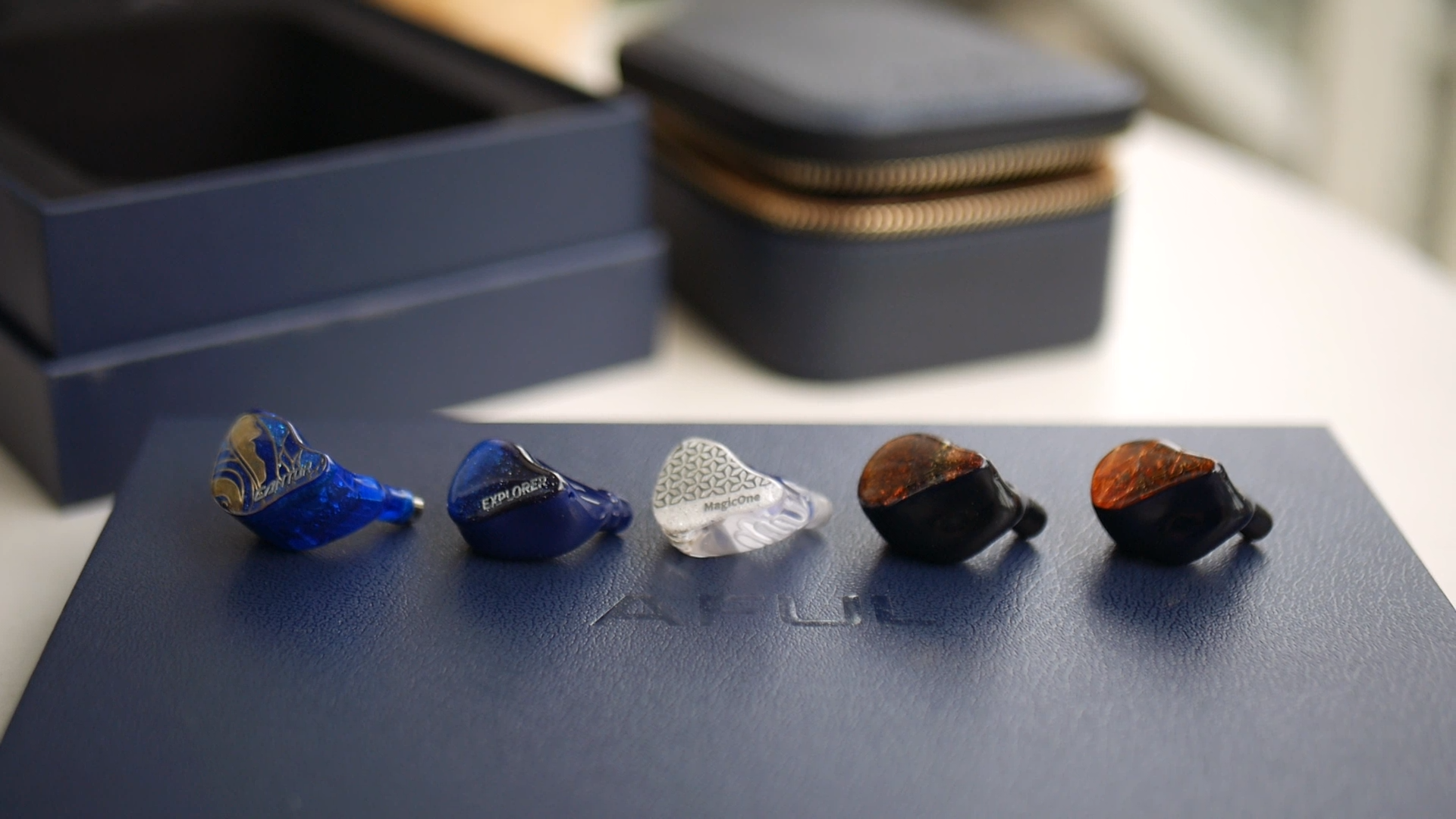

The inner box feels a bit fancier than previous AFUL IEMs. It feels subtly luxurious, though certainly not as over the top as some other high-end IEMs. Inside the box, the packaging is rather minimal and efficient: both earpieces sit in their own slot whilst all other accessories are kept inside the carrying case.

Accessories is where Cantor improves upon its siblings. The usual plastic puck case is replaced by roomy faux leather case with soft velvet lining. The stock cable also looks and feels nice with cloth sleeve, custom metal hardware, and leather cable tie. I enjoy this cable quite a bit because it is does not hold memory and easy to handle. My only complaint is that the cable is rather microphonic. One way to address this microphonic problem is to use the built-in chin slider to tighten up the cable around your neck.

Regarding ear tips, AFUL supplies 3 types of ear tips with different hardness. They influence how the IEM fit and thus can have varying degree of influene on the sound.

Ear pieces design: I was rather surprised to find that Cantor’s earpieces are not that large. Whilst it is thicker than all previous AFUL IEMs, the part that actually sit against the ear concha is only on the medium side of the spectrum, and noticeably smaller than many other high-end IEMs.

Now, let’s talk about the part that draws the most concern and skepticism: the nozzles. Without ear tips, the nozzles indeed look scary due to the length and the protruding metal tube. However, I would say these pictures are misleading. Here is why:

The metal tube is completely hidden by most ear tips, besides very short and wide ones such as Divinus Velvet Wide Bore and Sancai Wide Bore. In other words, the empty space between the end of the nozzles and the opening the ear tips, which is always there on other IEMs, is filled in by the metal tube. Thus, when you put the ear tips on, the total nozzle length of Cantor is no different from other IEMs.

Fit, comfort and isolation Despite the scary-looking nozzles, I found that Cantor is one of the more comfortable IEM because its nozzles are rather slim. To me, slimmer nozzles mean less pressure on the ear canal, meaning more comfort in long listening sessions.

Speaking of long sessions, I’m happy to report that I did not experience any pressure build up even when I use the IEM as background music for many hours continuously. Despite the pressure release mechanism, noise isolation of Cantor remains quite high. It handles bus rumble and street noise quite well.

Ear tips recommendation: In order to get the most out of the treble response of Cantor, you need to wear this IEM deep enough. As most IEM with strong treble extension, if you wear Cantor in a shallow fit, the treble would become harsh and piercing.

How deep is enough? I say you would need medium to deep fit, but not necessarily as deep as the infamous Etymotic fit. In other words, if the cap of the ear tips sit comfortably at the first bend of your ear canal, you are good. If the ear tips barely hang onto the opening of your ear canal, you are going to have treble problem.

By changing the depth of the fit, you can control the trade-off between treble smoothness and soundstage width. In general, shallower fit means wider perceived soundstage and harsher treble. Grippy ear tips can help you achieve better seal, which lead to thicker bass response. For me, my optimal ear tips are the stock medium tips.

Sonic Performance

Testing setup:

- Sources: iBasso DX300, L&P W4, FiiO K7

- Cable: stock cable with 4.4mm termination

- Ear tips: stock medium ear tips.

The subjective impression is captured using the lexicon in the Sound Wheel below. I’ll clarify the terminology as I use them. If you want to see more details of the lexicon and related reference, please have a look at the technical report ITU-R BS.2399-0.

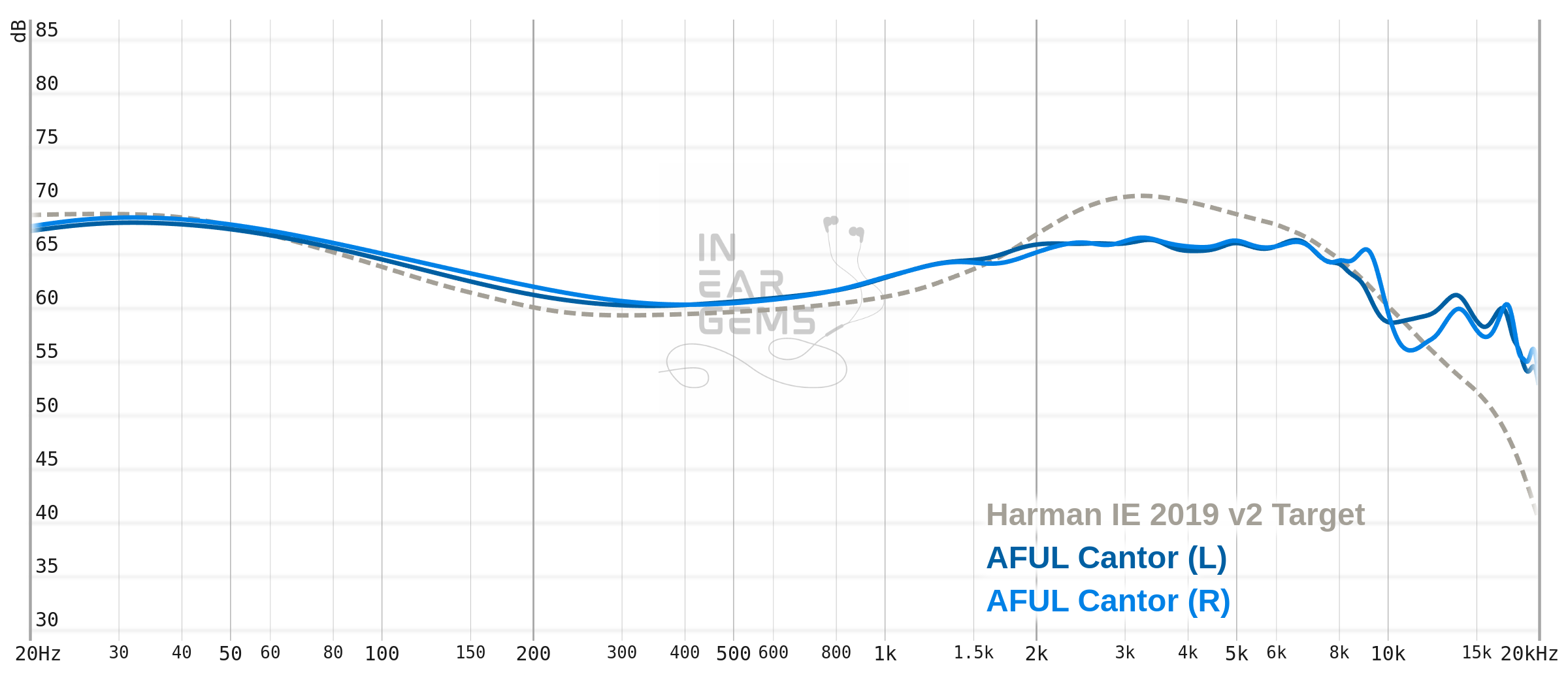

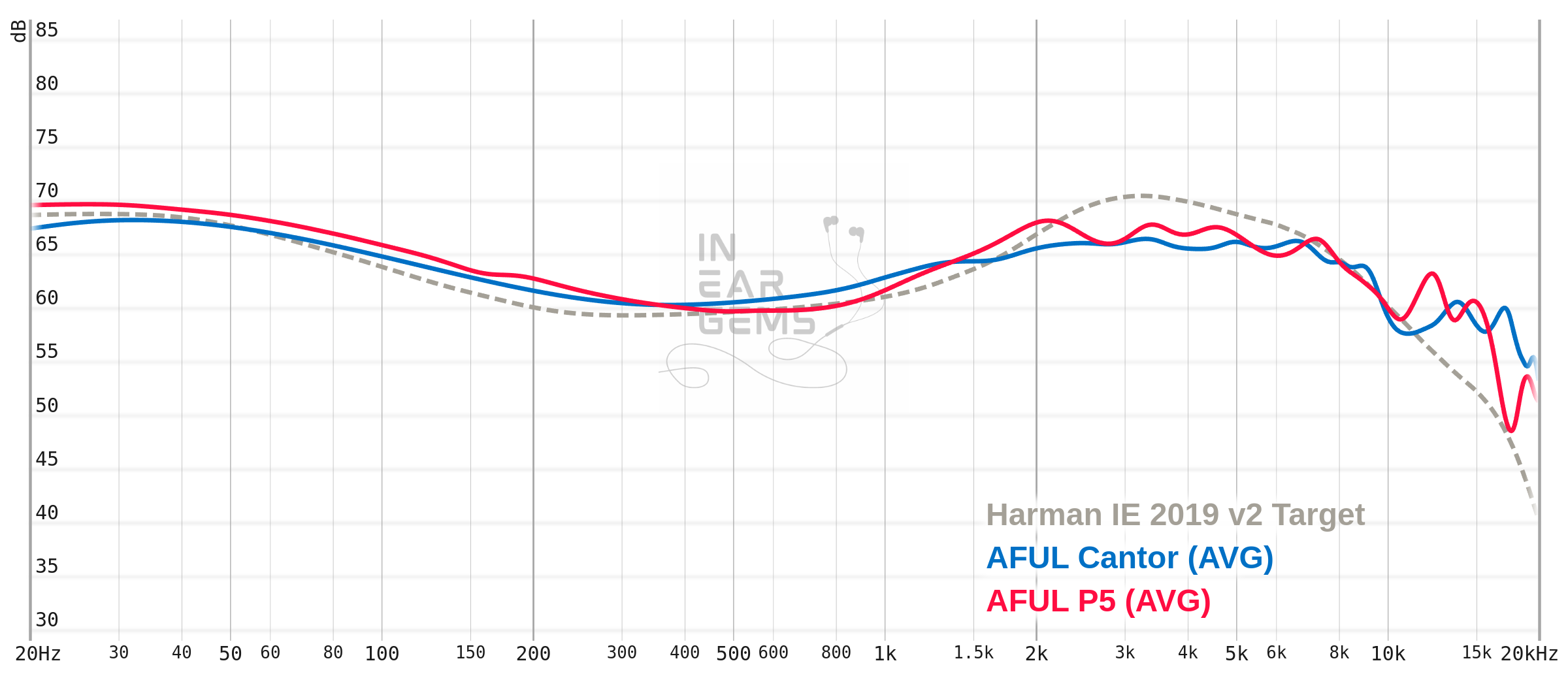

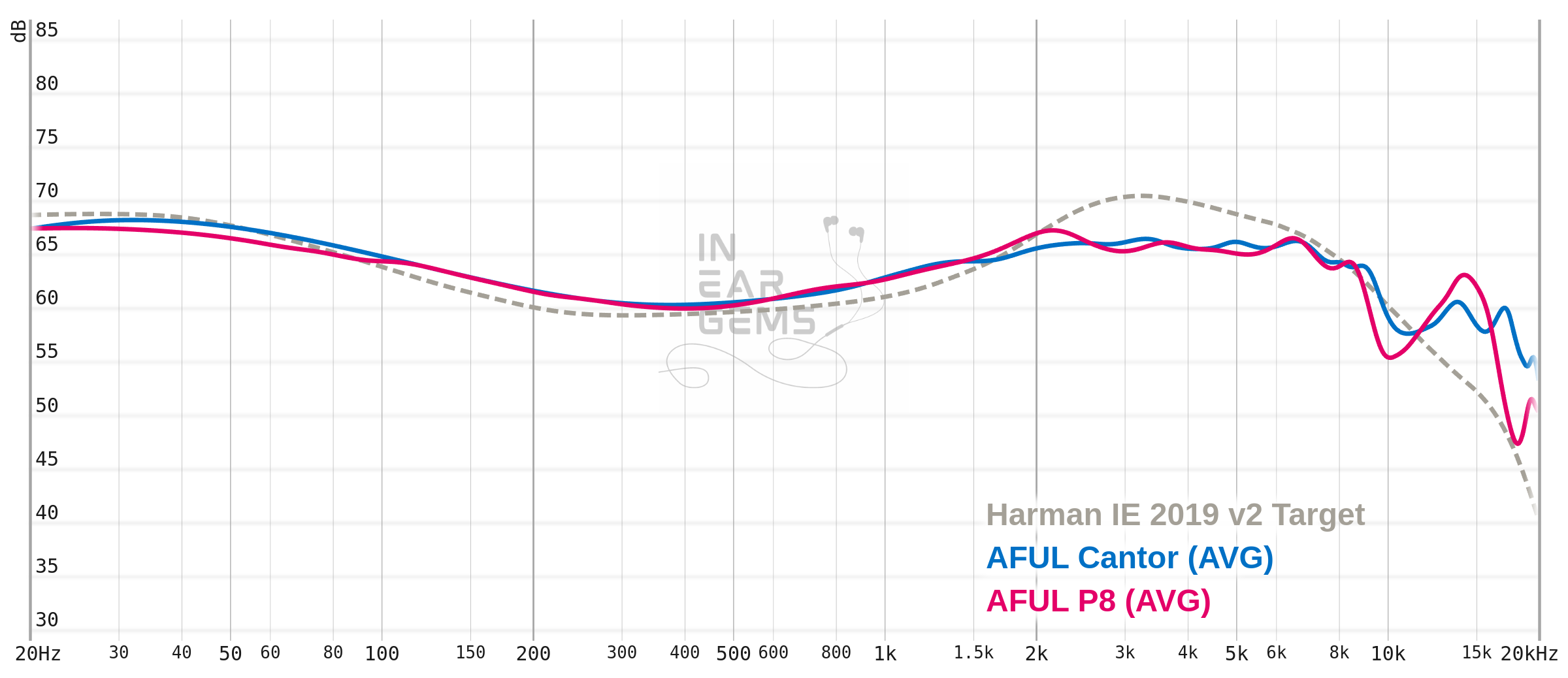

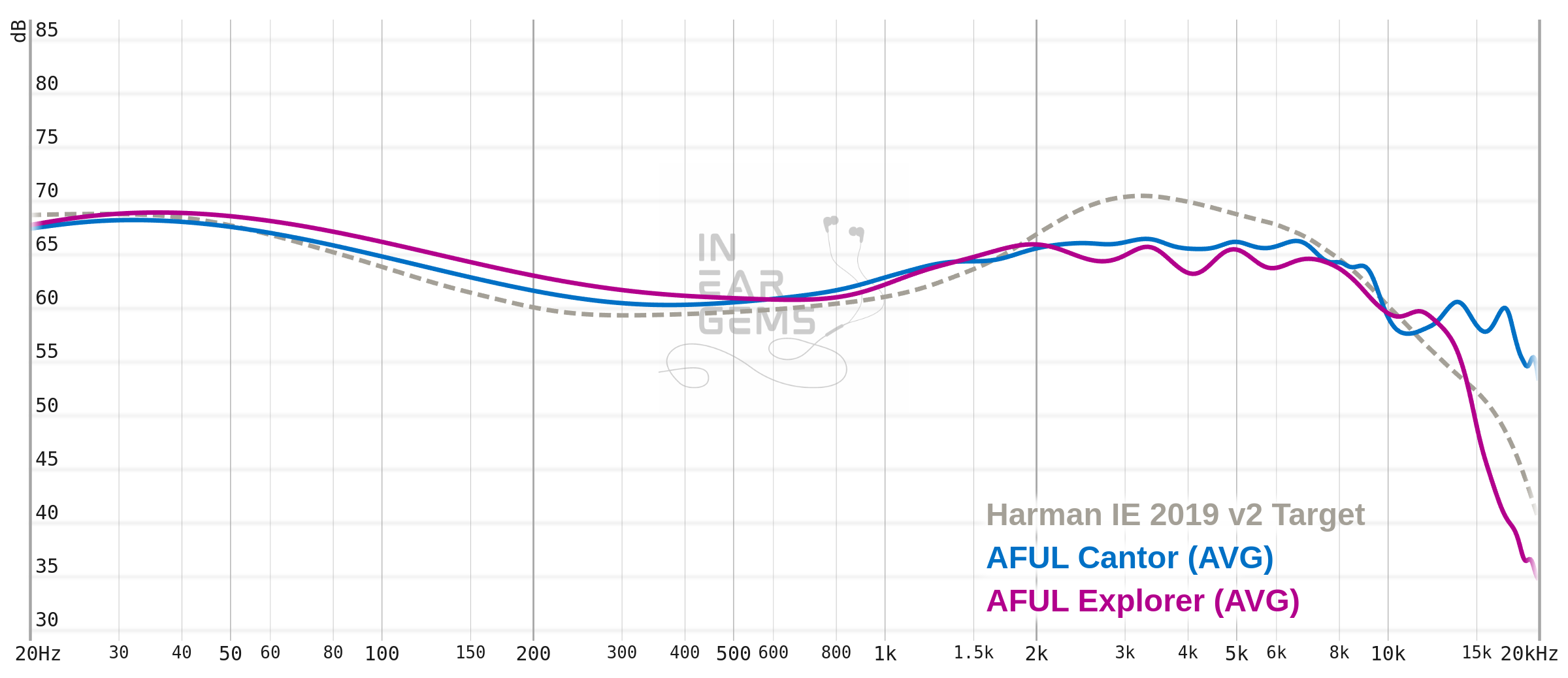

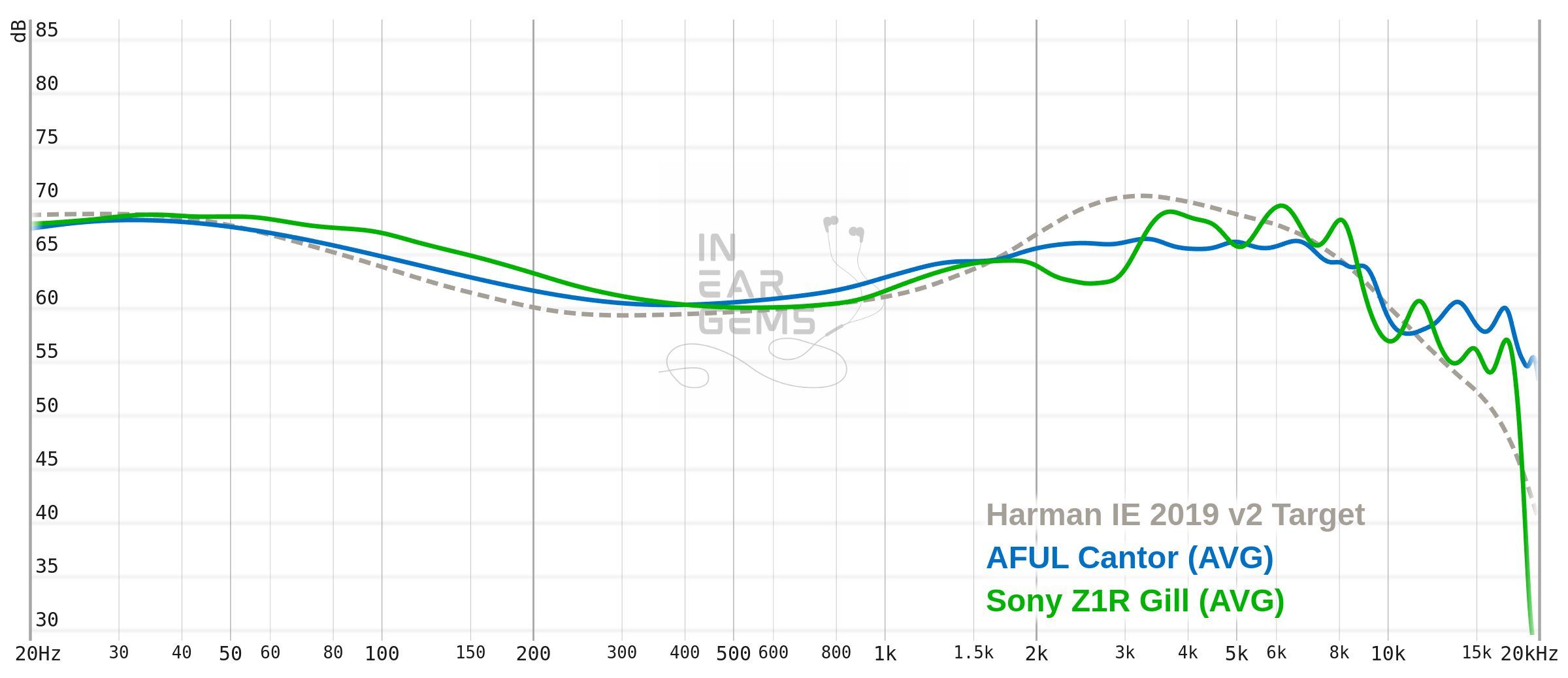

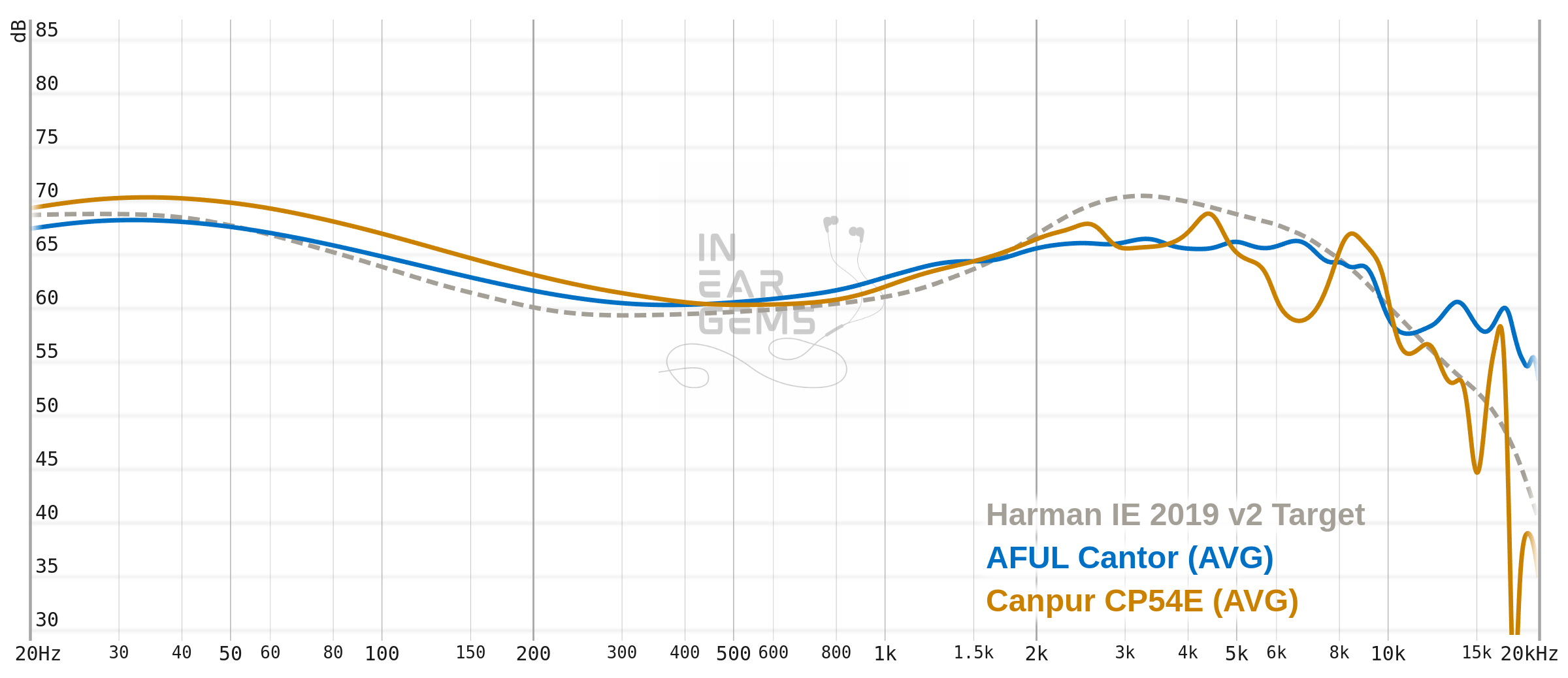

Timbre: It is helpful to think of an IEM as a filter that highlights or subdues different parts of the incoming audio signal. This effect can be measured objectively by the squiggly lines below, called Frequency Response (FR) graphs, which measure how loud an IEM is at different frequencies from 20Hz (bass) to 20kHz (upper treble). Subjectivity is how your ears and brain interpret the effect of that filter on your music and decide whether it is “enjoyable.” There are some “rules of thumb” when it comes to tonality, but most interesting IEMs usually bend the rules masterfully.

Figure shows the frequency response of Cantor against the Harman in-ear target. Measurements were done with an IEC-711-compliant coupler and might only be compared with other measurements from this same coupler. Above 8kHz, the measurement likely does not match the response at the ear drum. Visit my graph database for more comparisons.

The tonality of Cantor is rather difficult to describe due to how colorless it is. The most relevant adjectives that I can use to describe cantor’s sound would be transparent, balanced, and natural. I find this IEM tend to disappear when the music starts because I hear the music rather than hearing the colouring of the IEM over the music. All voices and instruments sound like how they should be. Different parts of the frequency respones in a mix, be it difference lines of a piano solo recording or different instruments in a rock band, are properly balanced against each other. If a recording is supposed to be bassy or thumpy, it would sound bassy and thumpy with Cantor, and vice versa.

If I try to give a more “technical” description, I would say Cantor has a mild W-shaped sound signature, meaning it emphasises the subbass, midrange, and upper treble with a good sense of separation between these frequencies. In particular, I found that voices and main instruments of most recording tend to be brought forward rather than pushed behind the bass and treble. At the same time, the midrange does not overpower the rest of the response. The accuracy of Cantor’s response means that different mixes can have noticeably different instrument balance, rather than sounding similar.

Let’s go into details about how Cantor present various types of voices and instruments in some test tracks. The first track is Shivers by Ed Sheeran, which is invaluable for checking the harshness and sibilance of an IEM, as well as its balance across the midrange frequencies. Cantor does not intensify the harshness in this track, but at the same time it does nothing to reduce the sharp edges either. I quite enjoy the way Cantor renders Ed Sheeran’s voice in this track. It does not add a blanket of warmth on this voice but also does not tilt his voice toward upper midrange to make it thin and shrill like some full Harman or diffuse-field based IEMs.

The next track is Kiwi wa Boku ni Niteiru by See-Saw, which is an excellent song to test the ability of an IEM to handle female vocals in “weeb musics.” Cantor does a great job here, making the voice of Chiaki Ishikawa bright and clear, while maintaining enough energy in the lower midrange to avoid making the voice thin and harsh. I also enjoy how crystal clear the rest of the mix is, allowing me to hear all other sound elements making up the background of the track. I was quite surprised by the amount of detaild packed into this familiar track when I listened to it with Cantor the first time.

The next track is Now We Are Free by 2CELLOS, which assesses an IEM’s ability to render lower-midrange, particularly cellos. Cantor passes the “2CELLOS” test with flying colour. The main cellos have a thick and authoritative tone with proper “weight” and low-pitched rumble, without sounding muffled or muddy. I’m particularly impressed by the ability to Cantor to handle the lower midrange of this track, which is quite saturated due the presence of two cellos and the cello and doublebass sections of the orchestra. Cantor managed to maintain the definition of and separation between these instruments, preventing frequency region from becoming muddled.

The next track is Playing God by Polyphia. I focus on the tonal quality and the level of energy conveyed by the guitars. This track also helps assess the balance of the bass against the midrange, which is reflected by the relative loudness between the bass guitar and the rest of the music. There are two aspects that Cantor impressed me with this track. The first aspect is the sheer texture and detail of the bass guitar. I can hear a distinct low-pitched growling of the bass guitar. It’s powerful and present whilst also maintaining impressive level of control and details. The second aspect that impressed me was the percussions. The kick drum has clean yet powerful attack. Cymbals and hats are energetic enough and full of micro details without becoming harsh or piercing. At the same time, Cantor does not pull the treble back, so you might find the treble a bit too high if you are after a warmer and milder tonal balance.

The next track on our list is the aria of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, recorded by Lang Lang. I find that piano is the best instrument to assess the overall tonal balance of an IEM. Simply put, if the piano does not sound even across the frequencies, the midrange of an IEM is imbalanced. Cantor renders the piano with a great sense of balance across the spectrum. None of the voice unnaturally overpower other voices. Moreover, the sense of clarity and separation is remarkable, making it very easy for me to “zoom” into individual voice and then “zoom” out to hear how all voices interact with each other. In some parts, such as at the end of Variation 2, I can even hear the sounds of mechanisms inside the piano. Another area where Cantor does a great job is the ability to fully convey the dynamic of the recording, smoothly transitioning from piano to forte with all the shades in between. Simply put, the IEM manages to grab my attention and refuses to let go throughout this long piece.

The next track on our list is Ciaccona from Bach’s Violin Partita No.2 in D Minor, performed by Kavakos. This track aims to assess two aspects: the rendition of violin and the reproduction of upper treble energy, which is reflected by the quality and detail of the reverberation and micro details at the decay end of violin notes. Cantor presents the violin with a dry, clean, and textured tone. I like how the violin seems to pop up from a deep black background, surrounded by the reverberation of the recording hall. I particularly enjoy the slower phrases where the main violin notes stop slightly to let the reverberation rings out. The ability of Cantor to render those reverberation cleanly until the fade out does a great job of drawing me into the recording. Another area where Cantor impresses me is ability to convey dynamic variations and contrasts with many shades and gradations.

The final track on our timbre test is Synchro BOM-BA-YE by Tokyo Kosei Wind Orchestra. This track aims to test the tonal balance and timbre of the upper midrange and treble region. There are two cues I focus on in this track: the hand claps at the beginning, and the tonal quality of all brass instruments throughout the track. Cantor passed this treble timbre test without much difficulty. The hand claps at the beginning sounds natural and detailed. All brass instruments sound like how they should sound.

In summary, I find Cantor to have an impeccable tonal balance and timbre that does well across variety of musical content. It does not impose its will nor change the energy level of the recordings. Instead, it does the best job of getting out of the way of whatever audio content it reproduces. 5/5 - Outstanding.

Bass and perceived dynamic:

Many of us in our hobby tend to cringe when hearing the dreaded “BA bass”, which is generally rightfully so. I sometimes use the rather impolite term “BA fart” to describe the “classical” sound of BA woofers: clear attack but lacking any sense of “weight”, power, or rumble. In other words, bass notes sound like “poof”, the bassline feels hollow and truncated without proper texture or detail. Some tuners try to compensate by increasing the midbass, which, in my experience, only exacerbate the problem. Thus, I was skeptical when learning that Cantor relies on sophisticated tubes and crossover to improve BA bass rather than switching to dynamic drivers (DD).

It turned out my concern was unfounded, as the bass response and dynamic are the highlight of my experience with Cantor. Simply put, with Cantor, I don’t hear “BA bass” or “DD bass” but the actual percussive and bass instruments in the mix, if that makes sense to you. This impression is supported by two factors. Firstly, the bass attacks have crisp edge, as you would expect from a BA-based design. Where Cantor differs is its ability to provide the oomph to the bass attack, thanks to the subbass boost. As a result, Cantor’s presentation feels snappy, rhythmic, and dynamic. Or, simply put, it’s “toe tapping”.

Secondly, the subbass boost plays an important role in pulling the rumble, textures, and details in the bass line out. Perhaps thanks to the agility of BA drivers, Cantor does a great job at pealing the bass line apart and presents all of this information clearly. I particularly enjoy bass guitars, doublebasses, and lower strings of cellos with Cantor: the plucks of these instruments feel weighty and tactile, whilst their textures and decays are clearly presented in a way that not many dynamic driver woofers can convey.

The main limitation of the bass response to me is the amount of bass being presented. Simply put, Cantor has a strong vibe of “it is what it is” when it comes to the amount of bass you can hear. If a track is supposed to be thick and bassy, it will sound thick and bassy, and vice versa. Whilst this approach has merits, there are times when I simply want an excessive amount of bass for pure fun.

Let’s examine the bass and perceived dynamics of Cantor with some test tracks. The first one is A Reckoning in Blood from The Ghost of Tsushima OST. The crescendo at 01:10 highlights the ability to convey dynamic of Cantor. It’s like, there is no holding back. The energy level keeps rising steadily from the quiet section at 0:40 to the explosion at 1:10, which gets my blood pumping immediately. The subsequent beats from 02:50 are strong, snappy, and precise, conveying a great sense of rhythm.

The next track is Strength of a Thousand Men (Live) by Two Steps from Hell. This track highlights both strengths and weaknesses of Cantor’s bass response. Regarding bass quality, Cantor continues to shine as it can convey a sense of “grippiness” and texture in the bass region, making the bass line growl rather than low-pitched hum. Thanks to the control over the bass response, Cantor manages to keep the beats snappy and incisive on top of the rumble. However, the amount of bass of Cantor holds it back from a successful rendition of this track. Simply put, whilst I can make sense of the bass line with effort than usual, I don’t feel my blood pumping and toe tapping with this track with Cantor. To be fair to Cantor, few IEMs manage to well with this track in my experience.

So, what is my conclusion about the bass and dynamic of Cantor? I think there are many aspects that Cantor does exceptionally well, such as how it conveys dynamic swings, how it peels apart bass lines, and how it renders the textures and details of bass instruments. Where it tumbles is recordings that are not that punchy but we expect them to be punchy. Because Cantor does not boost the midbass significantly, these tracks end up sounding less energetic than what I expect. Still, tracks like these are far and few, and I find the pros to outweight the cons. 5/5 - Outstanding.

Resolution: To me, “resolution” can be broken down into three components: (1) Sharpness, incisiveness, or “definition” of note attacks (see the figure above). (2) The separation of instruments and vocals, especially when they overlap on the soundstage. (3) The texture and details in the decay side of the notes. The first two give music clarity and make it easy to track individual elements of a mix. The last provides music details and nuances.

Resolution is, without a doubt, the strongest aspect of Cantor. Transparent and effortless are the good adjectives to describe Cantor. Across tracks and genres, I find that Cantor always maintain a crystal clear clarity from bass to the treble without resorting to artificial sharpening of note attacks. The resolution on display here is what I call “true resolution.” What’s does that mean, you ask? It is the sense of effortlessness, when you listen to a dense and complex recording and find yourself able to separate and track individual parts with ease even whey they overlap on the soundstage. Moreover, when you zoom into individual element, you can hear minute details that lend those voices and instruments a great sense of realism.

Let’s elaborate on the resolution of Cantor with some test tracks. For the first track, we again listen to Ciaccona from Bach’s Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, performed by Kavakos. As a mentioned previously, Cantor does an outstanding job with this track. I like how the violin seems to pop up from a deep black background. The notes are not overly smoothened, but textured like how I hear my violin in real world practice sessions. I particularly enjoy how the reverberation extends out from the note and slowly fade into the background without being aruptedly cut off. In comparison against the venerable 64 Audio U12T, my benchmark for outstanding resolution, I found Cantor to be slightly more detailed and articulate. However, the gap is quite miniscule. Cantor also compares favourably against modern flagship-class IEMs such as the Canpur CP54E with an array of 4 electrostatic (EST) supertweeters from Sonion. When I listen closely, I find the CP54E to be half step ahead Cantor in terms of the definition and articulation of violin notes as well as the details of the reverberation and decay.

The next track is the “controlled chaos” ABC feat. Sophia Black by Polyphia. With this track, I focus on an IEM’s ability to not crumble under the complexity of overlapping layers in the mix. Cantor breezes through this track, making it easy for me to hear everything, down to the very faint overdub by Sophia Black on the side channels right from the opening of the track. As someone who loses attention quickly, I find Cantor turns these complex tracks into a game: what details can you pick out? Against the U12T, I found that Cantor is at least half step ahead. For instance, the busy section around 01:20 feels more veiled and congested with U12T. Interestingly, the CP54E does not out-resolve Cantor with this track. It’s likely that the V-shaped tuning of CP54E overshadows the advantages brought out by its quad EST array.

In summary, Cantor is an outstandingly resolving IEM that allows you to hear everything in the audio content. 5/5 - Outstanding

Stereo imaging and soundstage: Stereo imaging or “soundstage” is a psychoacoustic illusion that different recording elements appear at various locations inside and around your head. Your brain creates based on the cues in the recording, which are enhanced or diminushed by your IEMs, your DAC, and your amplifier. In rare cases, with some specific songs, some IEMs can trick you into thinking that the sound comes from the environment (a.k.a., “holographic”)

I’m surprised by how much I actually enjoy the soundstage and imaging of Cantor. Why surprise, you ask? It is because AFUL decides to stick to the same soundstage presentation as their previous flagship, the Performner8 (P8), a presentation that I did not enjoy. The best way to describe this soundstage shape of P8 is imaging having the foreground of the soundstage (i.e., singers, main instruments) pushed forward to your face. Because of this presentation, the soundstage can feel closed in and shallow, even if the IEM has great treble extension that can project the background elements far out (i.e., “large” soundstage in traditional sense). What surprised me is that despite sharing the same soundstage style, Cantor somehow manages to side step all of my previous criticism with the P8.

Precise and spacious are the best way to describe the soundstage and imaging of Cantor. The soundstage of Cantor can change readily between recordings rather than sticking to a particular shape. If a recording is supposed to sound intimate, Cantor can place the singer right up to the face or even inside the head. If a recording is supposed to sound like a live recording with a band or an orchestra, Cantor can place the voices and instruments as if they spread out in front of me. Depending on the recording, sometimes the height dimension of the soundstage is also used with instruments floating up and above the head. With most recordings in my library, Cantor can comfortably push the background elements of the mix out of the head. In fact, sometimes when I listen to Cantor on commute, I wonder whether other people around me can hear my music, due to how “out of head” the soundstage feels.

Cantor also makes excellent use of its large soundstage. It is quite adept at conveying the contrast between nearer and further elements of mix, creating a clear sense of layering. The imaging of Cantor is also tack sharp and precise. I’m particularly impressed by how this IEM reveals and convey minute shifting of the positioning of instruments, such as when the soloist moves slightly in front of a stereo mic. Needless to say, gaming is excellent with this IEM.

Let’s listen to some test tracks to assess the soundstage and imaging capability of Cantor. The first one is Original Sound Effect Track - Memory from Gundam Seed Destiny OST album. This track compiles all sound effects used in the show, arranged atmospherically and immersively. Cantor effectively utilizes this information to create a diverse soundstage, with sound elements appearing in all three dimensions, offering contrast between near and distant sounds. Many elements on the left and right channels will seem to originate outside the ears. Against the venerable 64 Audio U12T, my benchmark for outstanding soundstage and imaging, I’m surprised to find how much sharper the positioning of sound elements is with Cantor. Despite not having as much air vent as U12T, Cantor manages to do a similar job at extending the soundstage to outside the ears.

The next track is Shadow of Baar Dau. This one tests an IEM’s ability to convincingly convey the sense of distance of background elements, such as the string section at 00:20 on the front left and the vocal chants on the front right at 00:40. Cantor successfully conveys a spacious sensation and creates an illusion that some background elements come from outside the head. I also find that Cantor has sharper instrument positioning than U12T. However, the slightly blurry presentation of U12T some how make the sense of space and distance in this track more “real” to me.

In summary, Cantor does an outstanding job at conveying a precise and spacious stereo image. Even as a self-proclaimed soundstage connoisseur, there is not much I can fault Cantor. If I really nitpick, I would say the soundstage of Cantor lacks a certain “special sauce” that some IEMs with the so-called Bone Conduction Driver can convey. Perhaps Cantor II? 5/5 - Outstanding

Driveability

Cantor has a moderate impedance of 20ohm and moderate sensitivity of 106dB/mW @ 1kHz. These specifications place it in the sweet spot of most portable DACs and amplifiers. To put in context, it is sensitive enough to avoid pushing amplifiers into current limit, yet insensitive enough to avoid hissing with most sources, even desktop devices like my FiiO K7 on high gain. I do hear an improvement when pairing Cantor with stronger source device, but I don’t feel like I sacrifice a lot of sound quality driving Cantor from smaller DAPs like HiBy R3. Alternatively, I can add a battery powered portable amplifier between my DX300 and Cantor to enjoy additional soundstage expansion and dynamic when I enjoy the IEM at home. Such versatility makes Cantor a candidate for a one-IEM setup.

Comparisons

AFUL Cantor vs AFUL Performer5: There were quite a few surprises when I compared Cantor and Performer5 (P5). My first surprise was the lack of volume difference. I can swap between these IEMs without changing the volume setting on my DAP at all.

The second surprise to me was how much more defined and rhythmic the Cantor feels compared to P5. For instance, whilst P5 can convey the dynamic swings such as the first beat drop at 01:10 in A Reckoning in Blood from The Ghost of Tsushima OST, the swings are not stronger than those of Cantor. Moreover, the attack of the drum beats are more loose and less incisive with P5. As a result, Cantor sounds more snappy and energetic than P5. To add a knock out blow, the bass texture and details of Cantor is also noticeably ahead of P5. I would say the performance showcased by these two IEMs flew in the face of the dogma of our hobby that DD woofers are automatically better than BA woofers.

The rest of the performance differences between Cantor and P5 were not surprising. For instance, Cantor is more resolving across the frequency spectrum. Imaging is more precise on Cantor. The best way I can explain the difference in the presentation of these IEMs is that P5 feels cloudy when I listen to it immediately after listening to Cantor: the background is not as dark, elements do not pop from the background as clearly. When instruments overlap, it is harder to separate them. That said, this cloudy sensation ceases to be that problematic after I listen to P5 exclusively for a few songs.

AFUL Cantor vs AFUL Performer8: When swapping from Cantor to Performer8 (P8), I immediate noticed four differences. Firstly, the P8 was louder than Cantor at the same volume level, though not significantly more so. To put in context, I need to drop the volume from 28 to 22 on my DX300.

The second difference was how much flatter the soundstage of the P8 feels. To be fair, both IEMs push the entire midrange forward to the listener in the same way. Moreover, both IEMs can separate the background elements (e.g., choral and string sections) from the foreground elements (e.g., main instruments and vocalists) and throw the background elements further into the background, away from the listener, thus both can sound spacious with the right track. The key difference is in the way these IEMs shape the foreground layers of the soundstage. Simply put, the foreground layers have more “thickness” on Cantor, meaning I can pin point nearer and further elements within the foreground of the mix (e.g., the singer is slightly closer whilst the main guitar is further back). On the other hand, P8 tends to compress the foreground layers into a relatively flat plane.

The third difference was how much more defined the outline and boundary of elements on the soundstage are with Cantor. For example, when I listen to soundtracks from The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, I found that Cantor can make every instrument on the stage crystal clear and well separated, as if they pop from a black background. Meanwhile, everything feels more “blobby”, less define, more cloudy, and the background feels more “gray-ish” with P8. As a result, it’s harder to track and focus on individual parts of the mix with P8. When I “zoom” into individual parts of the mix, I found that P8 reveals less details and nuances than Cantor.

The final difference was bass and dynamic. The difference was rather day and night when I listen to A Reckoning in Blood from The Ghost of Tsushima OST with both IEMs. The dynamic swings, such as the first beat drop at 01:10 was much more powerful and satisfying with Cantor. Every following beats are also more incisive with Cantor, giving the track stronger sense of energy and rhythm. The texture, details, and rumble of the drums are also noticeably better on Cantor. The difference persisted even when I turn the volume of P8 to be noticeably louder than Cantor to give it an advantage.

AFUL Cantor vs AFUL Magic One: Most of the differences between Cantor and other AFUL IEMs that I applied above apply to Magic One as well. For instance, Magic One sounds noticeably more cloudy and less detailed than Cantor. When the beats drop, Magic One does not sound as visceral as Cantor. However, I can hear the DNA of Magic One’s bass tuning in the response of Cantor with the emphasis on tight and crisp note attack to convey a strong sense of rhythm (a.k.a., the infamous term “PRaT”). Surprsingly, I also found Magic One to convey less information in the treble air region than Cantor, making Magic One a more mid-range centric performer compared to Cantor. Regarding sensitivity, Magic One is noticeably harder to drive than Cantor.

![]()

AFUL Cantor vs AFUL Explorer: This is the comparison that I look forward to the most, as Explorer is one of the most accomplished bass performer in AFUL line up before Cantor, in my opinion. So, how did Explorer fare?

Let’s put the obvious out of the way. Yes, Explorer sounds more cloudy with less details and poorer instrument separation than Cantor. Surprisingly, I have no problem with the sense of space of Explorer when listening to spacious recordings such as the Ghost of Tsushima OST or Samuel Kim’s epic covers.

What surprised me the most was the bass response. Given that Explorer is a bass-centric IEM, it was expected that Explorer has louder bass than Cantor. What’s interesting is how Explorer controls that bass response, ensuring that dynamic swings are well presented and bass attacks are snappy. More importantly, Explorer also manages to convey details and textures in bass instruments, not unlike Cantor. Whilst Cantor’s bass is ultimately more precise and refined, I can totally understand if you find a small loss in bass quality in exchange for more indulgent bass quantity presented by Explorer a better choice.

AFUL Cantor vs Juzear 61T Butterfly: You might be asking “why this comparison?” Well, one of the answer is “why not”, but the more accurate one would be curiosity. Given that 61T is an IEM that I consider a “unicorn”, I am quite curious how it fares against the Cantor, and I guess you do too.

The first difference between these IEMs was the tuning. If you consider 61T to be “neutral”, then you would find Cantor “cold” or “analytical”. Alternatively, you find Cantor “neutral” or “reference”, you would find 61T a bit too warm and muffled. Personally, I think both IEMs fall within the realm of “neutral” and both present the music in a quite natural manner. Resolution-wise, I find 61T to be quite cloudy after listening to Cantor. This difference is a combination of lower instrument separation and the masking of lower midrange. Regarding the bass, 61T has a larger bass amount, but the bass is not as snappy and detailed as Cantor. You can think of Cantor’s bass presentation as precise jabs whilst 61T’s bass is like being wacked on the head with a pillow. Your preference would determine which bass presentation is better. Regarding soundstage and imaging, I found that 61T and Cantor are quite close in terms of the shape and size of the stage, but Cantor is noticeably more precise with better layering effect (contrast between nearer and farther sounds in a mix).

AFUL Cantor (Stock tips) vs Sony IER-Z1R (Sony silicone tips): Z1R is a legendary IEM when it comes to bass quality and soundstage (and also the difficulty of getting a good fit). How does Cantor fare? Using my favourite test tracks, the Ghost of Tsushima OST album, I put Cantor and Z1R on the scale. The first difference I observed was loudness: Z1R required 33/100 whilst Cantor needed 30/100 to reach the same listening volume. I’m slightly surprised by how closed the volume levels were, given the reputation of Z1R as a difficult to drive IEM.

The second difference was the resolution, in terms of both instrument separation and micro details. Whilst Z1R was certainly capable, Cantor consistently out-resolved it. Simply put, whilst both IEMs can separate and reveal all main elements in a mix effectively, Cantor goes one step further in terms of the little details of those instruments and of the fainter background elements. In other words, there are more information to listen to with Cantor whilst I run into a “veil” earlier with Z1R. This different is especially evidenced in slower but more detailed section such as the flute and string section between 0:40 to the crescendo at 1:00 in A Reckoning in Blood from The Ghost of Tsushima OST.

The next two differences were rather surprisingly to me. The first one was in the bass response. For instance, let’s consider the penultimate track in the album, The Fate of Tsushima. This track has rather interesting bassline with a sequence of drum beats panning back and forth on the soundstage, accompanied by low pitch “growl” from what I assume some forms of acoustic bass. When it comes to the amount, or loudness, of the bass, Z1R wins hands down. It is simply more thumpy and satisfying, though I would argue that Z1R does not boost the bass that much so if the track is not bassy enough, this IEM would not change that. When it comes to bass quality the scale tips back towards Cantor, again, by a small margin. Both IEMs present the bass line with a great sense of rhythm and dynamic thanks to snappy note attacks. Both IEMs presents the low pitch information and texture very well, most notably in the low-pitched rumbles. So in some senses, Z1R is impressive by how tightly it controls its massive DD subwoofers, whilst Cantor is impressive how it manages to convey bass energy with plain old BA woofers.

The final difference, or rather lack of difference, between Z1R and Cantor was the soundstage. Both IEMs craft similarly spacious soundstage that expands in all three dimensions. Cantor pushes the main content at the center of the soundstage forward more, whilst Z1R pulls the midrange back a touch, so in terms of the structure of the soundstage, I prefer Z1R’s. However, Cantor takes back the lead when it comes to the incisiveness and precision of the placement of instruments on the soundstage.

AFUL Cantor vs Canpur CP54E: The first difference between these IEMs were sensitivity. AFUL consistently requires 5 to 8 more volume notches on my DX300 to reach the sound loudness level from the balanced output. The second major difference was tuning. AFUL is a neutral / flat IEM whilst CP54E is a V-shaped IEM. In practice, CP54E sounds more punchy and energetic with boosted bass punches and sharper note edges. On the other hand, this tuning also casts a warm “veil” over the midrange of most tracks, giving vocals a warm hue that might be you might consider “musical”. Another side effect of this warm veil is reducing the sense of separation between instruments in complex track, making CP54E seem less resolving than Cantor. It is really not the case since CP54E actually has sharper note definition and more detailed treble air than Cantor when both IEMs play a sparse recording, such as Bach’s violin partitas.

_____

_____

Conclusions

If it hasn’t been clear, I thoroughly enjoyed my time with Cantor. It has been such a journey since the time AFUL teased the bass tube design of Cantor ages ago, and I’m glad the final result turned out as great as it is. Even though it does not break through the barrier of IEM performance set by the current state-of-the-art, it brings state-of-the-art sound to a much lower budget. The care and attention AFUL puts into the design and engineering of Cantor, the packaging that supports it, and, ultimately, the resulting sound quality firmly place Cantor in the pantheon of “TOTL”, in the humble opinion of this reviewer. Whilst we might never reach the “ideal” IEM, with Cantor and other IEMs that would inevitably emerge, I say we are getting closer and closer there, one release at a time. Seal of approval and recommendation without reservation.

Moving forward, there are but two questions. The first question is for you: how much do you need a highly technical IEM with a flat tunning in your collection?

The second question is for AFUL: What’s next, now that you are done with the full-BA topology?

What I like about this IEM:

- Ability to peel apart complex recordings

- Transparent, natural tonality that gets out of the way of music

- Vocals are realistic yet beautiful

- Clean and snappy bass transients

- Detailed and textured bass notes

- Large soundstage with laser sharp imaging

- Comfortable in long listening sessions

- Excellent accessories, especially the cable

What could be improved:

- Limited ear tips compatibility due to the built-in metal tube

- The bass quantity might be lacking with some tracks

- The soundstage lacks certain “special sauce” of IEMs with bone conduction drivers

Absolute Sonic Quality Rating: 5/5 - Outstanding

Bias Score: 5/5 - I love this IEM!